I always get excited whenever someone says “I have a dumb question” and this one came from Faye, a student in my “Baroque Flamenco Bootcamp” online course where harp players learn to play a dramatic showpiece of mine called “Baroque Flamenco.”

She wrote:

“Dumb question: In the chat on Sunday you said, “the underlying rhythm is a Mexican triple waltz,” (two fast 3’s and a slow 3) — do you mean just the underlying rhythm of the variations? Are the transitions and Melody etc back to regular emphasis on the first beat…?”

OK … so I’m taking a leap here by posting this for general consumption – but I’m really interested to know whether this answer is interesting to …well … uh … normal people.

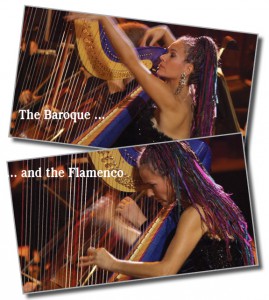

She’s talking about the rhythm that underlies the ‘Flamenco’ parts of my piece “Baroque Flamenco” – and for you Flamenco experts out there, I’ll just admit right now that this NOT a traditional Flamenco rhythm but … well, whutEVur … my poetic license is up-to-date, I’m pretty sure.

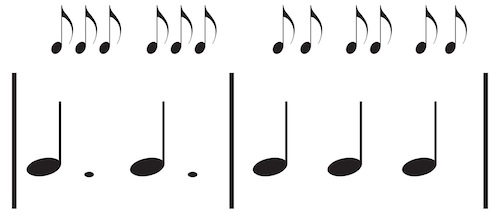

The rhythm looks like this, with the little top notes being the way we hear it and the bottom notes being how we write it (and don’t worry if you can’t read music … it doesn’t matter to this story, but I’ll show you anyway).

Here’s my answer:

I haven’t really thought about this before, but from what I can tell, that triple-waltz rhythm is only in the variations … and also – in the orchestral version – it comes back at the very end, when the Baroque MELODY is played in that Flamenco rhythm.

As if the melody and the rhythm that were once separated by the structure of the piece fell in love and became one.

That’s how it happens in the orchestral version (which you can watch here, as I conducted it last summer with the members of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra with the inimitable harp soloist, Eleanor Turner, playing the harp part)

It’s a long story about why I didn’t write the solo version that way — but it really had to do with the fact that the cadenza becomes so HUGE that there’s no way you can get bigger after it – unless you have an orchestra — so my choice was to go small again.

One Expands INTO

In the ORCHESTRAL version, the rhythmic ‘story’ is that the cadenza basically inspires or teaches the melody its own passion, and the cadenza EXPANDS INTO a passionately reinvented version of the Baroque melody.

So, the melody learns to express itself with passion.

That story may only be important to me – and I hadn’t thought about discussing it in the course until you asked this question.

The other Transitions FROM

In the SOLO version the cadenza TRANSITIONS from very big to a very tiny version of the melody, and then re-expands to the final coda.

So in both cases, the CADENZA expands in rhythmic, emotion, drama, physicality and sheer decibels. In fact, the cadenza is EXACTLY the same in both the solo and orchestral versions.

But what happens at the END of the cadenza is completely opposite in the solo and orchestral versions.

Why? Because the orchestra can make that moment bigger. Way bigger.

In the concerto version (i.e. the orchestral version) the orchestra entrance is the payoff. The Harp Cadenza incites the orchestra entrance and it’s gloriously BIG and joyous when the harp and orchestra play the final melody tutti, huge and utterly infused with that triple-waltz rhythm. And from there it gallops to the final, dramatic coda.

Sadly, there IS no orchestra when you play it solo. So I went in the completely opposite direction. I created a transition out of that huge cadenza that leads to the smallest, tenderest version of the melody I could write. And from there it expands again into the final dramatic coda.

You can watch Eleanor Turner playing it solo, in a barn, in this video.

The reason I’m explaining all this instead of just answering your question is that I didn’t ‘compose’ the piece with any of this in mind. I invented it – and continue to reinvent it – by trying to get as close to the emotional story as possible. If you know the story, you can make choices about how to play it and interpret it and make it your own.

The Character is Expressed

So the CHARACTER of the melody is expressed in 3/4 Minuet, and the CHARACTER of the variations is expressed in Mexican triple waltz and the CHARACTER of the cadenza is expressed in repeated phrases that use rhythm, percussion and aggressive, relentless strumming to build tension, and the CHARACTER of the transitions is to shift us between these in whatever way ‘works’ at the moment, either rudely slapping us from one character to the other, or sinuously pulling us from one character to the other.

So the CHARACTER of the melody is expressed in 3/4 Minuet, and the CHARACTER of the variations is expressed in Mexican triple waltz and the CHARACTER of the cadenza is expressed in repeated phrases that use rhythm, percussion and aggressive, relentless strumming to build tension, and the CHARACTER of the transitions is to shift us between these in whatever way ‘works’ at the moment, either rudely slapping us from one character to the other, or sinuously pulling us from one character to the other.

And the point is to create a vehicle for us to embody and experience and express these characters of ourselves.

Now … back to rhythms …

One of the beauties of the relationship between the ‘rhythmic’ Variations and the ‘gracious’ Themes (or Melodies) is that the underlying tempo stays the same. You could play it with a metronome and still experience a dramatic shift from Melody to Variation.

The change happens because the beat is divided in a different way. The character of the music changes. The tempo stays exactly the same.

What I love about that from a musico-psychologic standpoint is that … hmmm … how can I explain this … if I’m identifying with the music (as in “I am this music I’m playing and it is me”), then each part of the piece is a part of me, a part of my character.

The melodies are something like my ‘classical, gracious, traditional, and — oh, I admit it — my controlled’ self and the variations are my wild, impassioned, I-love-to-stomp self – and the transitions are whatever needs to happen to shift me between them, to allow me to embrace each more fully and eventually to integrate them and express them fully.

As the piece progresses, the transitions get longer and less obvious (this wasn’t intentional, I’m just noticing it now), and the final melody – in the solo version – is almost a lament or a tenderness for the controlled-and-gracious me (the me that fits nicely and lovingly in a box – because there is that me) — and the ending is a complete triumph of the wild me.

But no … really it’s not a triumph of one over the other but an ILLUMINATION – a partnership, an expanded ability to be both, an acknowledgement that both can exist simultaneously in me.

You hear that especially in the orchestral version, where the final melody is played completely integrated and impassioned with the Mexican rhythm.

In the solo version, you hear the integration later – in the coda, which combines the classical convention (the straight 1-2-3) with the most dramatic of the Flamenco (but really Mexican … but actually more like a Mexican who’d seen a flamenco troop) strums.

These weren’t ‘compositional decisions’ in a preconceived sense – they were just what needed to happen to make it FEEL the way I needed – to inspire the EXPERIENCE. It was later on that I took it apart to ask myself how it worked.

So to answer your question … the transitions are the wild-card.

They may take the character of either the rhythmic variations or the gracious melodies. OR BOTH. They are transitions. So you can play around with them and see how they FEEL.

It’s probably important to know that, when creating the piece, I wasn’t thinking “and now I’m going to write a transition.” I just created the piece in a way that told me the story I needed to hear. Later, when I started trying to teach the piece to other people, I started breaking it down into parts and giving the parts these names.

So I hope that answers your question … and THIS is why I love dumb questions.

Don’t you wish the old masters would have described their music and emotions so when people play them the emotional power remained? Though the emotion in Beethoven’s Cannons is still hard to deny. Back when Satellite TV was free I used to watch “A Capitol Fourth” from DC each year and sometimes put it out on my big speakers… Those cannon were magnificent!

One of these days I might hook up those “Voice of The Theater” speakers and play your DVD for the neighbors and the store down at the highway intersection. That could be interesting. You could Rock the Mountains. I’m told that the Volcano is still active, but that is in ten thousands of years, or more. Perhaps …

Funny you should say that, Dave! I think a lot of them did it right there on the page – I always marveled that Debussy and Mahler (and I’m sure others) would sometimes write so much in the scores – almost like little stories, or stage directions about how they envisioned the music. But I must say that the option we have now – to connect direct (through the internet) to share a composer’s vision, and answer questions from players – it’s incredible!

That’s the least dumb “dumb question” I’ve ever heard. And an answer that makes me want to run to the harp and start trying things. This whole rhythm thing has been a downfall of mine for years – I’m pretty good at 4/4 but beyond that when I look at a piece of music and try to play what is intended I have a really hard time figuring it out – and this piece is a good example. Parts of it “feel” different than what I think I see on the page. Now I know why. And, by the way, I tend to go with what I feel rather than what I think I am supposed to be playing. Since I’m playing solo most of the time that works fine, but boy, did I have trouble when I started playing in groups. Sadly I can’t run to the harp, I’m off to work, but thank you for ILLUMINATING the way you think about this and put the pieces together in different situations – it helps!

Ohhhh … Betsy! We finally started figuring out how to address that in “Hip Harp Toolkit” Latin Style last summer, when Cristina Braga created a set of two-part lessons that each started with body percussion & dancing, and then moved to how to create the same rhythm on the harp.

You’re totally on the right track to start with what you FEEL (rather that what you ‘see’ as swimming, anxiety-provoking black dots on the page [er … I guess I’m probably projecting here, eh?]) especially when playing solo.

And yes, it’s tricky to play rhythms with other people that they either grew up with, or learned the conventions of so long ago that they don’t know how to break them down (and often don’t think they should have to … so you get that added bonus of shame).

Rhythm is actually such a deep subject – because it’s the shape and pulse of TIME, one thing we absolutely can’t hold or freeze to look at, and when it’s written out, it’s such an approximation of what’s actually happening that even when you get it metronomically perfect, you’ve just scratched the surface!

AND … I’m so glad my writing about it helps!! Thanks so much for letting me know.

DHC, thank you for this rich, intimate explanation of what’s behind BF. (I took your BF course – which was fantastic!) Unpacking how the artistry works is SO valuable plus it staves off the silly (but understandable) intimidation of a written page.

In the end, it is all about “feel” – what we feel like expressing – or whatever it is we ARE in the moment, coming through our medium (music.)

Also, thank you for making it “ok” for us to explore then notate what we need in our scores to reach for creativity.

You are so welcome, Cynthia! (and I had to laugh at your use of the word ‘staves’ in describing the intimidation of the written page … a beautiful pun!) and it was great having you in the course!!!