My mother married Burt Henson when I was … well, when I wasn’t yet. Soon, however, I was. But they weren’t for very long.

When I was seven she married Larry Conant and we started moving around the country. I was called Debby Conant then – at least, I was when I was with them.

But every summer, no matter where we were, I’d head back to California to run the circuit of grandparents, cousins and a two week stint with my other Dad, my first Dad, Burt. And in California I was called Debby Henson.

When we moved to North Carolina, my name change became coastal. On the East Coast my last name was Conant and on the West Coast my last name was Henson.

That coastal switch continued ’til I was about 12 when I said, “ONE NAME, please! It’s too confusing always switching.”

So they put the names together and my last name legally became Henson-Conant. I liked this. I wanted to be a composer and I liked Rimsky-Korsakov, and Henson-Conant was close.

By the time I was 16, though, ‘Deborah Henson-Conant’ was way too long, so I got the nickname of “DHC.”

Below are stories of my two dads – and the other men who fathered me as a girl. It was a joy and a heartbreak to write about them last night and to remember how much they mean to me, still , and how much they shaped my life, my humor and my music.

Burt Henson

Burt Henson was born on a farm in Escalon, California. He had a tough life and tough father. But he made it to Stanford law school and eventually became a judge. He loved politics, ran for Assemblyman in California and won. Eventually married a wonderful woman named Harriet who also loved politics and who was at one time the Mayor of Ventura, California, where they lived.

He played the banjo and he sang, and I loved his voice forever. We never spent much time together until about a year before he died, when he came to stay with me for a week and astonished my then-partner’s young son by eating ice cream for breakfast every morning. I’m glad I finally got to know him

Though I’d never spent much time with him, more than once in my life he told me I was bullheaded and stubborn, which I took to confirm that I was at least part Swedish.

He was concerned about my stage persona. Once he stood with me as a long line of audience members asked for my signature after a performance with the Baltimore Symphony. When the last person got to the front of the line, I introduced her to my Dad. She said, “Oh you must be so proud of your daughter,” and he said. “Well, I don’t know. Don’t you think she ought to tone it down a little bit?”

She thought he was joking.

Larry Conant and Samuel Hodes

When my mom met Larry Conant, he was teaching at UOP (then COP – College of the Pacific) in Stockton, California. I don’t know how they met, but they fell in love and married when I was seven.

We moved to a tiny town in the foothills of the Sierra’s: Hathaway Pines: Population 100. Goldrush country, Mark Twain country.

Larry worked as the school psychologist in Angels Camp or Murphys – one of the bigger towns – or maybe the whole county. My mother became a bookkeeper to Cyril Monteverdi, who ran the oldest steel foundry west of the Mississippi. Cyril was a kind man, married to Jen, a colleague of Larry’s – with a beautiful old house that had three pump organs in the living room which I was allowed to play whenever I wanted to — a clawfoot tub on the 2nd floor, lace curtains that danced in the breeze and a bannister Cyril taught me to slide down.

Cyril and Jen had no children themselves, and they welcomed us into their house with a quiet delight and left me deliciously to myself amongst all the magic of rusty gears, lace curtains, pump organs and swimming holes.

Larry started graduate school when I was eight, and we moved into the Amazon Housing Project in Eugene, Oregon – a former army barracks now full of kids, fascinating young couples from different parts of the world and one construction worker who claimed he could eat nails. At least that’s what he told me – and I swear I saw him do it at least once.

Larry once told me that where he grew up, in Wisconsin, it was so cold in the winter that your ears would freeze on the way to barber shop and that once he heard the barber’s shears clink on his ear. He told me he made a $25 bet during the Great Depression once with his uncle Roger that he could learn to play the first page of Für Elise in a week, even though he’d never played the piano and didn’t read music, and he won the bet.

When I started writing music and didn’t know how to notate music, he showed me a piece of staff paper. “Here’s where you write ‘middle C’ he said – and here’s where it is on the piano. All the other notes either go up or down.” And that was my piano lesson.

He taught me the trick of the the String in the Sugarwater – supersaturating water with sugar and hanging a string in it overnight so that in the morning it was encrusted with crystals. I’ve thought of that story so many times and built so much of life on it, always searching for the string in the sugarwater – the one connective idea that crystalizes everything around it – that I no longer remember what I remember.

But I do remember a spoon, a glass of warm water, stirring and stirring and discovering there was magic in that house when he was there.

Larry talked about ideas, let me play with Rorschach Inkblot cards and died suddenly one morning at the age of 48, in the back of the car on the way to the hospital. The last time I saw him he was on the phone saying he had a pain behind his sternum.

And that sweater he’s wearing in the photo – my mother knitted it. I was wearing my white majorette boots. But I wasn’t a majorette.

Samuel Hodes

Samuel Hodes was my mother’s father. Her whole life my mom and her sisters called him “Daddy,” and her two sisters still do. He could play two pieces of Classical Music on the piano: Moonlight Sonata and Humoresque – rare feats of musicality that were like magical appearances. Something you’d hold your breath waiting for – like a shooting star. Recorded music wasn’t a part of my life so this was my full experience of classical instrumental music.

Bill Reynolds

I wish I could find my favorite photo of Bill Reynolds, the man my Dad’s mother married after my Grandfather Dewey died. Bill was the man in my life who taught me about dry humor, and the only person who could make my Grandmother Edith laugh. “Edith,” he’d say, “It’s time for dinner. Take my hands to the bathroom and wash them,” and she’d giggle. “This isn’t funny, Edith. It’s a war injury. It’s nothing to laugh at. Stop giggling and take my hands off and take them in there and wash them.” And she would giggle like a young girl.

Cyril Monteverdi

A few years after Larry died, Cyril shyly courted my mother. His wife Jen had died years before. I only heard that he sent flowers, and that she hadn’t returned his affection. I was sad because I loved this man and his magical house with the clawfoot tub and the pump organs. And I loved his steel foundry and the whimsical droppings of steel he’d pick up from the floor and give me, giving them silly names like, “Look, here’s a horse put together by a committee!”. I loved the wayback behind the foundry: a vast yard of massive rusty gears and machine parts and how each seemed alive and colorful. I loved his kindness and how he seemed to delight in showing me things.

About 15 years after Larry died, I took a trip to Angels Camp and I went to visit the old steel foundry. The office seemed to be in the foundry itself and when I walked in the door, a woman looked up from her desk and said with much surprise, “Oh, my goodness! You’re the little girl!” I didn’t know what she meant. “The little girl in the picture on Cyril’s desk” and I saw, dusty, and small, a picture of me at seven that had been on his desk for nearly 20 years.

I’d like to think that some of those flowers he sent my mother were meant for me.

Happy Father’s Day Burt, Larry, Sam, Bill and Cyril. Thank you for fathering this little girl.

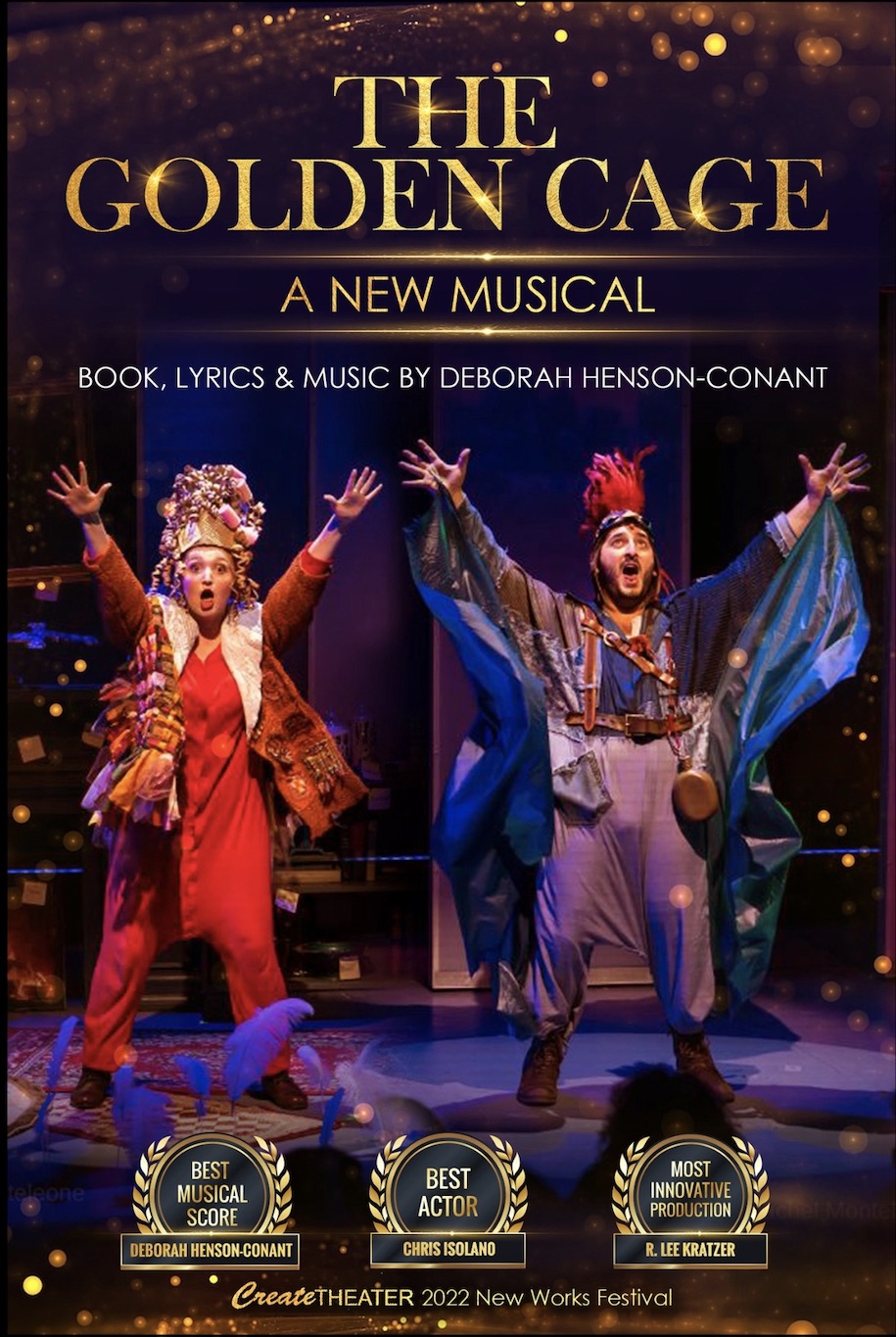

PROJECTS & PERFORMANCES:

FOR HARPISTS:

- Join Hip Harp Academy

- Harp Time Live (FREE Weekly Playalong)

- FREE Resources

What an absolutely lovely telling of the Henson-Conant lines. This is so sweet. WIth hugs from a father. Dan Beach

Thank you for sharing All of this! As a member of HipHarpAcademy You mesmerize my inspiration every time I can join in. Just learning the integration of music, Harp, and Authentic experiences with Zoom friends. An excellent Gift.

What a nice share!!!!! You made me like all these fathers in an instant. Lucky you, for having all these nice memories and being able to share them with us.

Hi Deborah, this is wonderful. Thank you for sharing. There are several things I have never known or didn’t remember: I didn’t know your Grandma Edith remarried. I never knew of Cyril Monteverdi. I never saw the photo of you with Larry and Grandpa. I love it!

Love, Auntie E

Thankyou Auntie! Yes, Edith met Bill on a cruise to Alaska and he was a funny and wonderful man who could wiggle his ears. I also think I may have spelled Cyril’s last name wrong – it might be Monte Verde.

Thank you for sharing, Deborah. What sweet stories of all of them and of you. I really enjoyed them.

Deborah, that is such an amazing story! Thank you for sharing such special memories this Fathers’ (note the plural form) Day!

What a beautiful story about your 2 Dad’s growing up. Interesting to get a glimpse into your life and how this has influenced what we see in you today. I wondered how you had the two surnames and so now I know. Thank you for sharing the photos and story that makes it all come alive.